The potter's wheel and the bow-drill, both of which

were in use in widely separated countries as long as 6,000 years ago, were the precursors of the machine-tools of today.

The earliest

type of drill was the hand drill which consisted merely of a smooth cylindrical stick having at one end a pointed flint. To

drill a hole the stick was rotated between the palms of the hand. This type of drill, but without the flint insert, was also

the earliest known method of making fire.

|

| Inuit using bow drill with chin pressure to drill ivory. |

Next came the strap-drill, which was the earliest

mechanized form of drill. A thong or strap was passed around the middle of the drill and the drill was rotated by pulling

the thong backwards and forwards. This method necessitated the use of two operators for, whilst one was pulling the thong

the other had to press down upon and steady the drill by means of a socketed holder on top. The next improvement was the bow-drill.

In this, the thong was still used to rotate the drill, but the two ends of the thong, were attached to the ends of a bow and

so enabled one operator to manipulate it. These two principles, that of the bow-drill and the strap drill, were later adapted

to the lathe.

The bow drill is one of the oldest types of drills developed by craftsman. There is much evidence that it was widely used

during the Egyptian times 3000 BC to drill holes in wood and stone. From the Old Kingdom we have illustrations which show

carpenters were using bow drills to bore holes in timber. A number of carpentry bow drills have been found that were used

by the ancient Egyptians. The bow was much wider at one end to allow for a handhold, and the drill-stock was made of wood,

and sometimes contained a discharge hole to help eject the drill bit. The capstone bearing was of wood or hard stone, and

had a hole in one end for the insertion of the drill-stock. The first known depiction

of the bow drill is in the 5th dynasty tomb of Ty at Saqqara; however, the tool must have existed earlier since a number of

bored wooden objects exist from the Early Dynastic Period.

|

| Drawing of hieroglyphics found in Egypt. |

Hand-powered stone borers were also used by the ancient

Egyptians for the hollowing of stone vases and representations are found in Egyptian art. The use of bow-powered coring drills

as a method of cutting rock is inferred from marks observed on ancient Egyptian stonework, and includes pieces of waste rock,

as well as finished and unfinished stone objects. Traces of verdigris, either copper or bronze, as well as abrasive, have

been found in core holes in both Egypt and Crete.

Modern Bow Drills

The bow

drill was a dominant boring tool until the invention of the brace during the Middle Ages.

|

| Simple bow drill with detached top which fits a point at the top of the metal spindle. |

When it was used for drilling smaller holes in wood the top of the wood

handle was pressed down with the operators hand.

|

| Bow drill with breast plate. |

But when large holes was needed or drilling

into tougher material like metal a breast plate was used allowing to operator to apply more pressure and even free up a hand

to hold the work. Over the years a drill bit was developed which allowed cutting action to take place in both directions,

thus improving the worker’s efforts.

By the 1850’s there were manufactured bow drills

of the highest quality. Buck of England is one of the premier bow drills of this time. Their use of ebony wood, with finely

machined internal spinning mechanisms, made them much desired by the finest craftsmen of the 19th century.

|

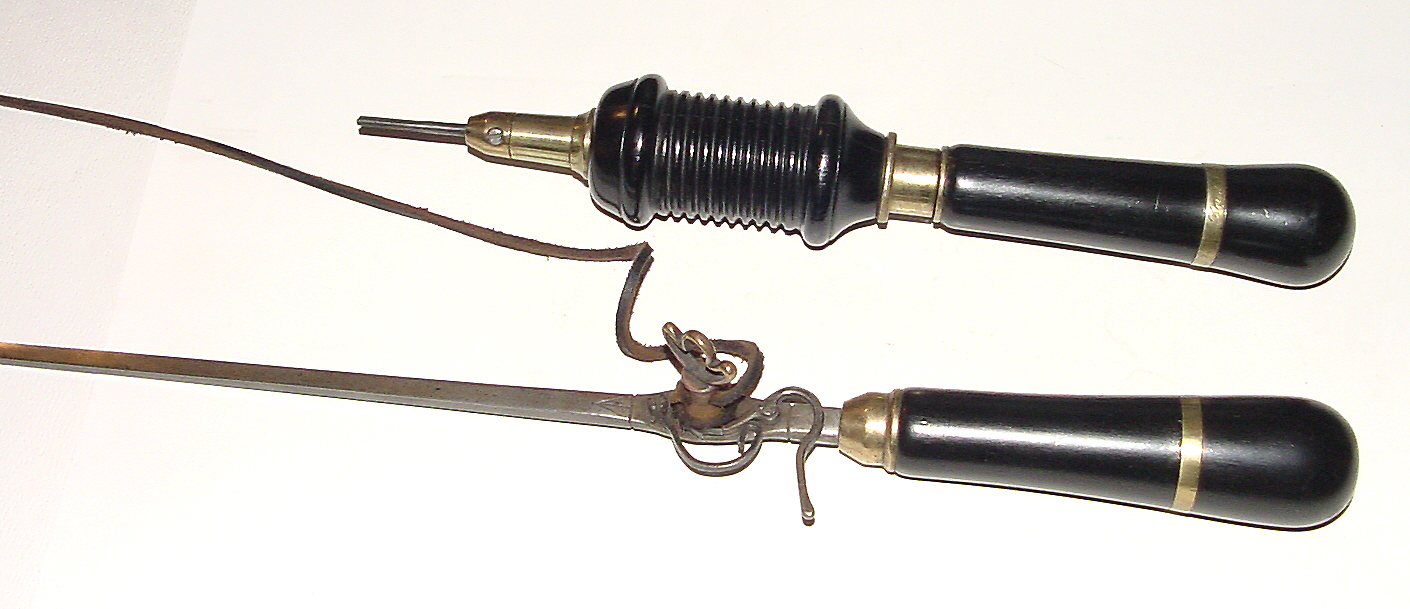

| English ebony bow drill with matching bow. Marked on brass ring, G. Buck Maker, 242 Tottenham Court |

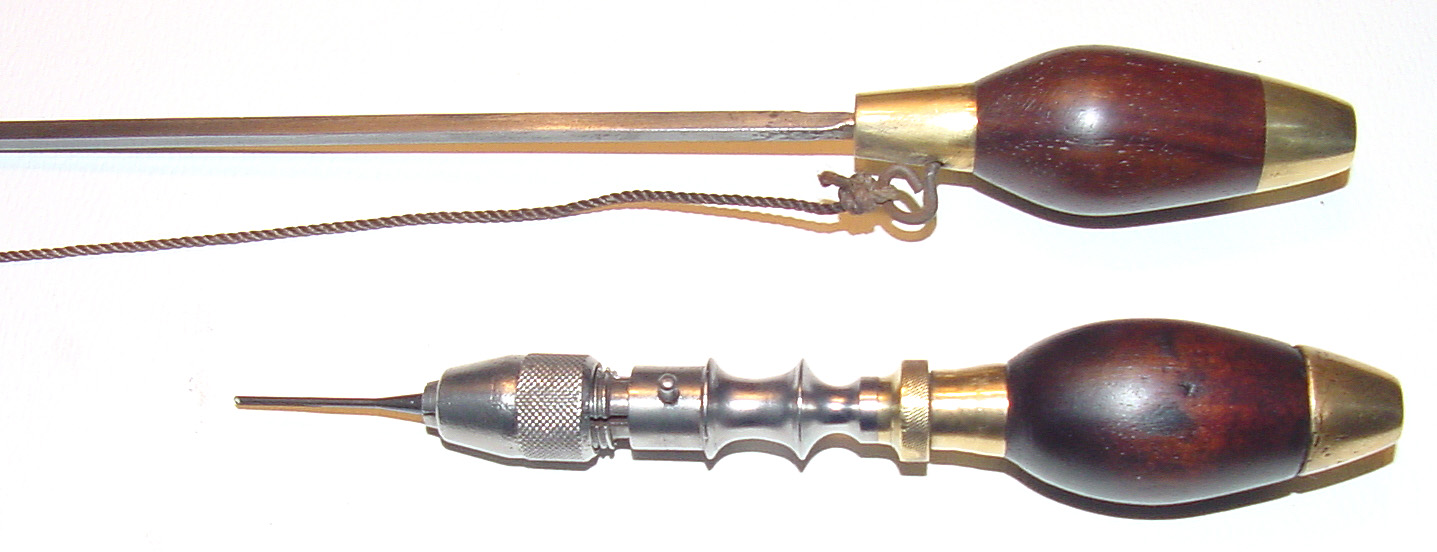

The Bow

Early bows of ancient resembled the hunting

bow of the era. But over time it was modified to more closely resemble the fiddler’s bow. Early versions were made of wood and easily fashioned by the user

of the bow drill. The cord was just tied loosely in a knot thru a hole at each end. Later a metal sword like bow developed

with a turned wood handle with the cord tied to a “S” bend on one end and tied to a metal hook at the handle end.

During the 19th century many different ratcheting devises were developed to tighten the cord at the handle end. Today these

intricate ratcheting bows are highly prized by the collector.

|

| Two different ratcheting bows. |

New York City Bow Drills

During the later part of the 19th century, there developed a tight-nit

industry of craftsmen in New York City who made tools for the highly specialized trade of piano and organ builder. Most well

known of these makers is Napoleon Erlandsen and his son Julius. Many examples of their bow drills exist today and are highly

prized by collectors. Erlandsen was by trade a machinist and his drills were precision made. They had steel main shafts with

ivory pulleys and rosewood handles. They were exquisitely machined and had a fine adjustment mechanism for fine tuning the

spinning action to eliminate wobble.

|

| Above top is drill marked R. Fishley, made similar to NY style drills. Second drill is stamped N.E., |

|

| Above and right is drill marked L. BRANDT, No. 220 1/2 5t St. N.Y. |

I have seen many of these and find they are often

marked differently if at all. I recently acquired a bow drill with a rosewood

pulley that was constructed similar to the Erlandsen’s drills. I was astounded when I took it apart and found the mark,

L.BRANDT, No 220 1/2 5T St. NY. Knowing Dominic Micalizzi’s research on Brandt had him born in Denmark in 1808, this

made him 23 years older than Napoleon Erlandsen.

|

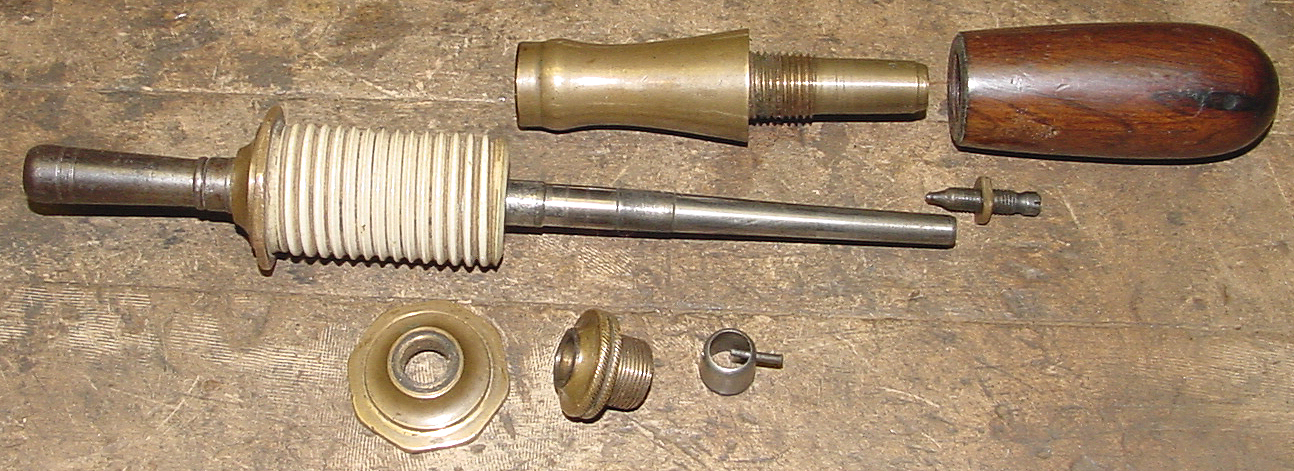

| Erlandsen ivory pulley bow drill apart showing main parts. Note needle point adjuster at top of spin |

Dominic also researched his 1850 to 1860 address to

be 220 1/2 5th St. Thus, this bow drill predates any Erlandsen drill by five

years as Erlandsen was not listed in the New York City Directory until 1864. In the many years after 1865, both Brandt and

Erlandsen shared working addresses. It would seem to me that Lauritz Brandt shared his drill making techniques with his younger

fellow tool maker Napoleon Erlandsen. Although I have to admit that Brandt’s bow drill exhibits more attention to the

design details.

|

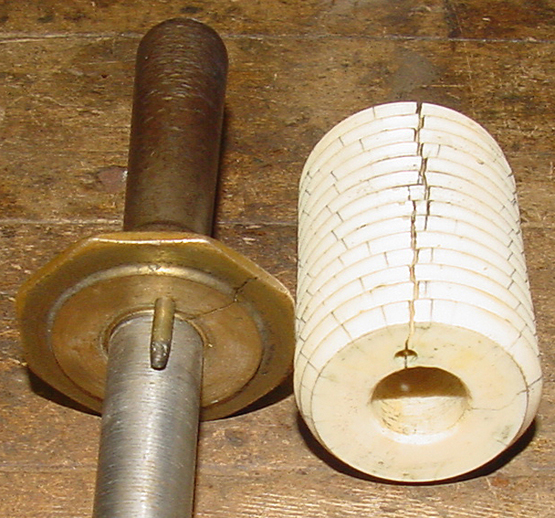

| Left-fixed pin inserted in ivory caused stress crack. Top right spindle has hole for pin that fits i |

One of the problems bow drill makers faced was how

to secure the spiraled ivory pulley to the spinning spindle. Taking apart some of Erlandsen’s drills reveals four different

techniques that were used. The simplest technique used was to press fit the ivory pulley tightly to the spindle while tightening

the brass hexagon nuts securely on each end. This was easy but usually the pulley loosened and adjustments were needed. Another

technique used a fixed pin in the brass octagon nut fitting into a matching hole in the ivory. A similar method was to have

a fixed pin thru the main revolving spindle which secured in a groove notched inside the hole of the ivory pulley.

|

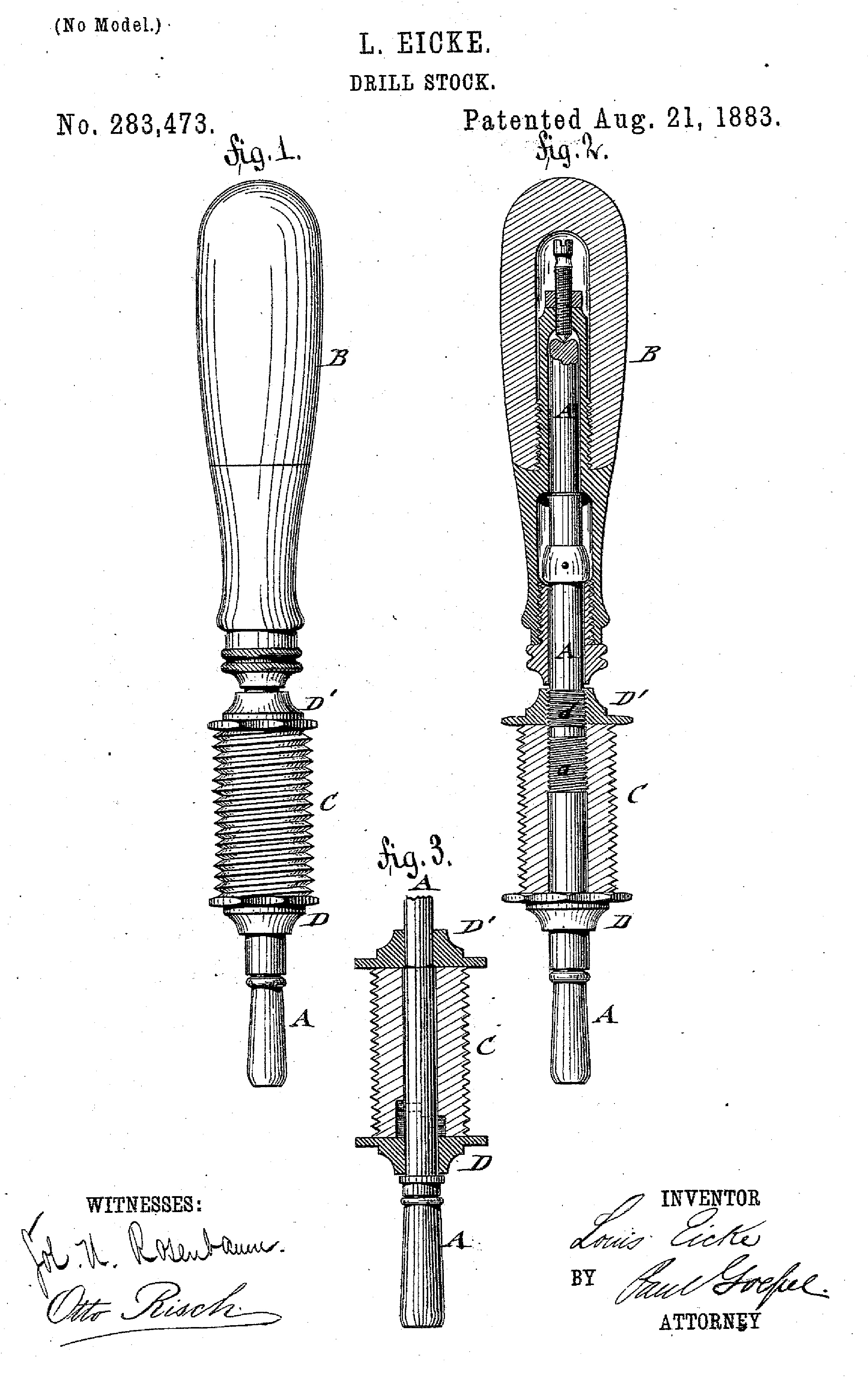

| L. Eicke patent No.283,473. |

Both of these pin methods secured the ivory pulley

but often resulted in cracked ivory from the resulting stresses. A patent by New York inventor, Louis Eicke, in 1883 solved

this problem by employing a threaded spindle which locked into internal female threads inside the ivory pulley. Erlandsen

used this design in some of his drills and indeed these ivory pulleys tend not to crack.

|

| Matching bow with drill. |

Part of the joy of collecting Bow Drills lies in the

abundant varieties of beautiful designs. There is a multitude of possibilities regarding design, materials, size, and operational

mechanics. For the collector who is also a craftsman, it is challenging yet rewarding to make a bow to match your finest drill.

Bow drills are one of mankind's first machines that has a long and important history. It would be lucky to find

one in a flea market or garage sale. They show up often at tool auctions, and the best demand high prices. It seems rarer

yet to find a ratcheting bow, never mind a matching set of drill and bow. Still the hunt goes on and I will welcome others

to join me in collecting and enjoying this significant tool of our ancient times.

|